The sole source for this article is a lesson plan from the U.S. Army Element, School of Music, 1420 Gator Blvd, Norfolk, VA 23521-5170. The lesson plan is entitled, "A HISTORY OF U.S. ARMY BANDS," Subcourse Number MU0010, EDITION D, 3 Credit Hours, Edition Date: October 2005. Provided below are excerpts from the lesson plan.

MILITARY MUSIC IN EUROPE

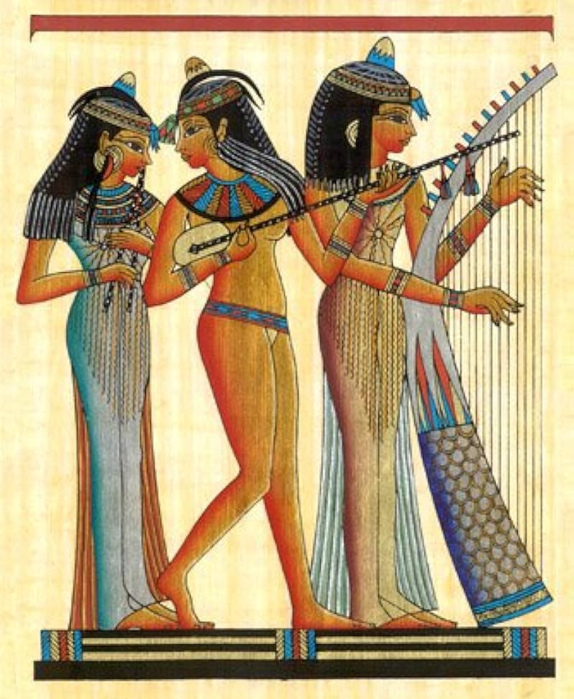

American military music derives many traditions and practices from European military music. Many of the earliest surviving pictorial, sculptured, and written records show musical instruments used by Soldiers in battles. Chronicles and pictorial remains from Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Oriental, American Indian, and other cultures depict trumpets and drums of many varieties used in connection with military activities (e.g., signaling in combat, during parades, and in encampments). Stone artworks (reliefs) from as early as 3,000 B.C. depict Assyrian and Babylonian musicians playing brass instruments while leading their armies in triumphal processions.

The earliest known illustrations of ensemble music are the brass, reed, and

percussion instruments shown on later stone reliefs. The Egyptians used music for ceremonies and entertainment around 1000 B.C. Reliefs from this period show musicians playing harps, sistrums (instruments that used rattling rods to produce a percussive effect), and nays (whistle-like instruments) for dancers and listeners.

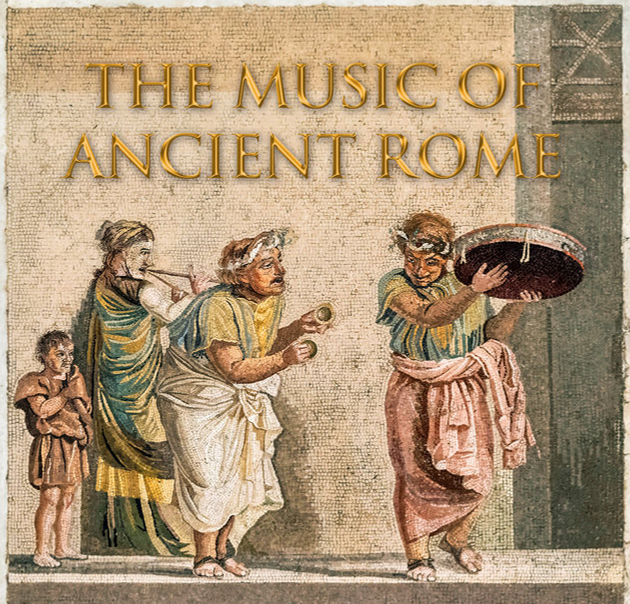

The Romans provide the first tangible evidence of organizational military musicians. Roman musicians, called aenatores, performed duties often required of military musicians today. They signaled troop movements, performed for official functions and funerals, played on the march, and provided morale support for the troops. The Romans provide the first known printed explanation for having military music, "To fire up attacking troops and to uphold their spirits while they endure privations and fatigue."

Moving forward to music in the Middle Ages, European Christians used horns and trumpets to lead their military expeditions against the Muslim Arabs during the Crusades (1096-1272 A.D.). The Arabs utilized a wide range of instruments. They utilized reeds, shawms (a double reed instrument), pipes (bagpipes), bells, cymbals, and an entire family of drums. This gave them the capability of sounding complex signals to communicate tactical objectives and troop positions, provide a rallying point for dispersing troops, and inspired fear in the enemy.

The Europeans returned from the Crusades with new musical ideas learned from the Arabs. They adopted the Tabor (a small snare drum found in Baroque music) and Nakers (kettledrums). The court music of England's King Edward III (1327-1377) included five trumpets, two clarions (an ancient English trumpet in round form), five pipes, three waites (horns), and a drum. The court of King Edward IV (1461-1483) consisted of 13 musicians playing trumpets, pipes, and shawms.

By the seventeenth century, the rank and social position of the European military musician had been clearly defined by the musicians' guild. He had become an esteemed member of the royal household, and the profession of a military musician was considered to be an honorable one.

MILITARY MUSIC IN AMERICA

Pre-Revolutionary War. Prior to the Revolutionary War, colonists readily adapted to British military traditions and rapidly accepted England's military ideas. They copied British militia organization, utilized British training manuals, and used British officers to drill their troops.

As far back as 1633, in the Colony of Virginia, drummers performed for marching practice during militia drills. In 1659, the Dutch supplied the militia of their new colony with drums. In 1687, the importance of music to the militia was further demonstrated when Virginia voted to purchase musical instruments for its militia. The first known band in the colonies was a band in New Hampshire in 1653 comprising of 15 hautbois (oboe) and 2 drums. In 1747, the Pennsylvania colonists formed regiments and Colonel Benjamin Franklin was the regimental commander in Philadelphia. In 1756, the Regiment of Artillery Company of Philadelphia, commanded by Franklin, marched with over 1000 men accompanied by "Hautboys and Fifes in Ranks." It is likely that the term "Hautboy" did not refer solely to oboes, but to military musicians, and that Franklin had a well-balanced band. This marks the first recorded appearance of an American military band in the colonies.

Music thrived in the colonies with the establishment of music schools, concert halls, and stores. Concerts were given in all the cultural centers. Boston papers advertised concerts as early as 1729. Josiah Flagg organized a military band of wind instrumentalist in Boston which performed at Faneuil Hall, becoming the pioneer band for performance of military music in America.

The Revolutionary War. After the Boston Tea Party (1773), the British antagonized the colonists by closing the port of Boston. To improve their defenses and prepare for war, the colonies formed Committees of Safety and forced Tory militia officers to resign. Officers sympathetic to independence replaced the Tory Officers. The colonists also accumulated stores of military supplies and established minuteman companies.

Musicians in the minuteman companies provided the steady rhythms needed to drill the new militia. On April 19, 1775, William Diamond (in some accounts Dinman), a drummer in Captain John Parker's Lexington militia company, beat "To Arms" at the Battle of Lexington. Also present was Jonathan Harrington, a fifer. Diamond later went on to march the Lexington militia to Bunker Hill. Sometime after Bunker Hill, Diamond set aside his drum in favor of a musket and served throughout the remainder of the Revolution, to include the Battle of Yorktown, as a foot soldier.

Within days of the Lexington battle, militiamen arrived in Boston from all the New England Colonies and eastern Canada. The Massachusetts Provincial Continental Congress requested aid from the Second Continental Congress to strengthen Boston's defense. As the delegates entered Philadelphia they were met by an infantry company with a band parading them through the streets of the city. The Continental Congress responded by establishing the New England Army and appointing George Washington commander of all continental forces. From the very beginning of the Continental Army, musicians have been included. The use of brass instruments varied by unit type, and valved instruments like the trumpet were not brought to fore until the mid-1800s.

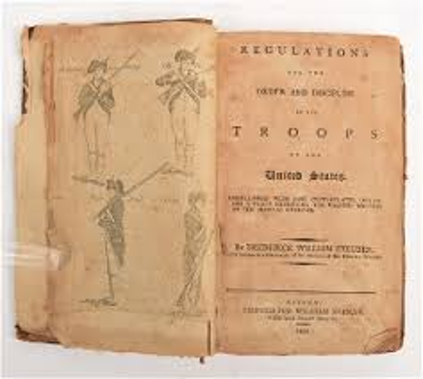

The First Army Regulation. General Washington appointed Baron Frederick von Steuben Acting Inspector General for the Continental Army at Valley Forge. Von Steuben wrote a manual of instruction that set forth a system of drill. He organized a special company that he personally drilled. Using that company as cadre, von Steuben trained the remaining troops. Washington, impressed by von Steuben's work, appointed the Baron to the permanent post of Inspector General and recommended the approval of von Steuben's manual for the entire Army. Congress adopted the REGULATIONS FOR THE ORDER AND DISCIPLINE OF THE TROOPS OF THE UNITED STATES on March 29, 1779. This manual continued and remained in its original form until 1824.

In the Continental Army, one fifer and one drummer were assigned to each company. They stood at the right flank of the first platoon. Drum calls regulated the Soldier's day. Since von Steuben's regulation did not allow verbal commands, each man had to learn to respond instantly to the drum. Chapter 21 of von Steuben's regulation was entitled “Of the Different Beats of the Drum.” It standardized drum calls and their functions into two categories: beats and signals. Calls directed to an entire encampment or sounded at specific times were called beats. Calls directed to only a portion of the encampment were called signals.

West Point. Throughout the Revolutionary War, colonial military officers trained their men from manuals that taught British tactics, strategies, and traditions. They quickly learned that British fighting methods were unsuccessful on hills, in forests, and against Indians. As a result, colonial forces adopted an Indian-like style of fighting (firing from behind trees, rocks, and earth-works).

During the Revolution, officers learned the new fighting techniques under fire. No formal training manuals or methods for teaching these new techniques were established. After the war, Congress recognized the need for a formal officer training program. In 1802, Congress established the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, as a training center for officers. From 1802 until 1815, the Military Academy had drummers and occasional fifers who performed in addition to their regular duties.

The Center for Military History (CMH) states that the official inception of the United States Military Academy (USMA) Band is June 8, 1817, but its history precedes that date. Authorized by the U.S. Congress on April 29, 1812, the initial hires of the Academy Band were three musicians: Silas Robinson, Martin Warner, and a Drum Major named George Washington. Various correspondence from General Joseph Gardner Swift - the first West Point graduate and the Academy's third Superintendent - indicate he was the primary reason a band was formed by the summer of 1815 and instruction under Kent Bugle, virtuoso, Richard Willis, the first "Teach of Music," began that winter in 1816. By the CMH’s official inception date in 1817, the band consisted of musicians on trumpets, bugles, clarinets, bassoons, cymbals, drums, flutes, serpents, and horns all performing under Teach of Music Willis’ baton.

The Army's First Band Authorization. In 1821 the Regular Army was reorganized. Legislative action ensured bands would also be part of the regular forces. Bandsmen were attached to regiments and allowed to draw the pay and allowances of privates. Regular Army officers were still required to provide the instruments if they wanted a band. Bands received their first official recognition and authorization to form as a separate squad in each regiment.

The Civil War. Five weeks after Abraham Lincoln's inauguration, Confederate Soldiers fired on Fort Sumter. The 1st Regiment of Artillery Band was present during the bombardment and surrender. This band was also known as Chandler's Band of Portland, Maine a civilian band volunteering its' service to the regiment.

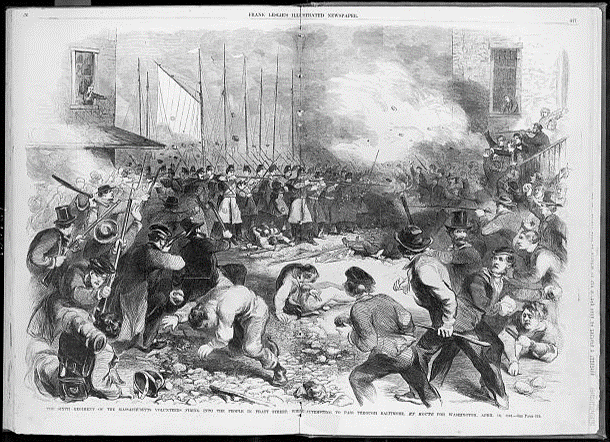

The first band to suffer casualties during the Civil War was the 6th Massachusetts Regiment Band. On April 19, 1861, the band arrived by train in Baltimore, MD. As the band left the station, a mob marching through the street attacked the band. The band fled, abandoning all equipment, as local Union sympathizers took bandmembers into their houses. The band suffered 4 deaths and 30 injured personnel.

As the war began, the U.S. military was as divided as the country. Many of the Army's finest officers resigned their commissions, returned home, and joined the Confederacy. Enlisted personnel from the southern states deserted the Union Army to fight for the South. d. Faced with severe personnel shortages, the Federal government allowed the states to establish their own recruiting and organizational policies. Many volunteer regiments recruited bands. Band recruiting was so successful that, by the end of 1861, the Union Army had 618 bands and more than 28,000 musicians.

The Continental Congress authorized each Regular Army regiment of infantry two principal musicians per company and 24 musicians for a band. Each cavalry and artillery regiment was authorized two musicians per company or battery. Each Artillery Band was permitted 24 musicians and each Cavalry Band was permitted 16 musicians. The Army was following the same practice as Weiprecht in Germany with distinct bands for each branch.

During the war, the duties of Union bands varied. They performed concerts, parades, reviews, and guard mount ceremonies for encamped troops. They also drummed soldiers out of the Army and performed for funerals and executions. The bands played for troops marching into battle, actually performing concerts in forward positions during the fighting. The martial and patriotic music the bands performed frightened the enemy and rallied Soldiers to victory. Bands were stationed at major military hospitals, lifting the morale of suffering soldiers. Bandsmen days were busy. Buglers sounded calls throughout the day. The musicians sounded the call for guard mounting at 0800 each day. Some regiments held dress parades twice a day, but most staged these events in conjunction with retreat ceremonies when regimental or brigade bands provided the music.

Between battles, Union and Confederate troops showed little animosity toward one another. Union soldiers often traded coffee for southern-grown tobacco. From behind earthworks, bands often played concerts, including the other side's favorite songs. On occasion, Confederate and Union bands would join in concerts when camped close together. A Union band gave a concert for the troops stationed at Fredericksburg, VA. After a playing a few favorite selections of the troops, a voice called from the Confederate positions across the river, "Now give us some of ours." The band played "Dixie," a favorite of both sides, "My Maryland" and "Bonnie Blue Flag."

The non-musical duties of bandsmen were primarily medical. Before battles, bandsmen gathered wood for splints and helped set up field hospitals. During and after the fighting, they carried the wounded to hospitals, helped surgeons perform amputations, and discarded limbs.

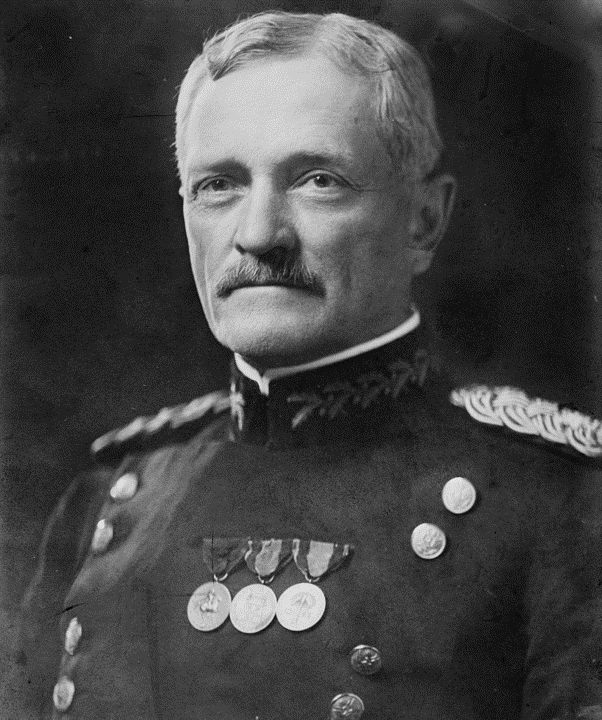

World War I, General Pershing and Army Bands. After the nations of Europe had been fighting for three years, the United States entered into World War I. General John J. ("Blackjack") Pershing was appointed as Commander of all Allied Expeditionary Forces in Europe.

Shortly after his arrival in early 1918, he and his staff discovered that the band music of France and Great Britain was greatly superior to that of the United States. Since General Pershing believed bands were essential to troop morale and supported them fully, he implemented a four-point program to improve the Army's band program:

(1) First, he urged Congress to increase the number of bands. Congress responded in July 1918 by authorizing 20 additional bands for the duration of the war.

(2) Second, acting on his own authority, Pershing increased regimental band strengths from 28 to 48 pieces. This provided Army bands with their first full instrumentation. The instrumentation for future Army Bands was set.

(3) He established a band school at Chaumont, France, in 1918 under the direction of Walter Damrosch (whose brother Frank had initialized an Army Bandmaster School on Governor’s Island, NY, five years prior). Its curriculum included an eight-week course for bandmasters and a twelve-week course for bandsmen.

(4) He commissioned all bandleaders as First and Second Lieutenants and sought to grant them an authority equal to their responsibilities.

In addition to his four-point program, General Pershing recommended a Drum and Bugle Corps be assigned to each infantry regiment. This was later approved.

The U.S. Army Band. As commander of the American Expeditionary Force, General Pershing heard bands such as France's Garde Replubicaine and those of the Household Guards Division in London. At the time, the U.S. Army had no band that could either equal or surpass our European allies or represent the Army in Washington, DC.

In January 1922, after becoming Chief of Staff of the Army, General Pershing ordered Captain Perry Lewis to form The U.S. Army Band. To best represent the Army, Captain Lewis realized he would need to gather the best musicians the Army had at the time. The Army Band quickly gained stature as a superior musical organization.

Army Bands in World War II. Approximately 500 bands served the Army during World War II. The bands were categorized into three types: special bands, separate bands, and organization bands.

The United States Army Band (Pershing's Own), the U.S. Military Academy Band, and the U.S. Army Air Corps Band were the designated special bands. As special bands, they performed at special ceremonies, concerts, parades, and recruiting drives.

Separate bands were controlled by the Adjutant General and supported the administrative, technical, and training centers to which they were attached.

Organization bands were under infantry units and were attached to combat commands to provide music for the unit's combat and support troops of the division. Regimental bands were abolished in 1943 as individual units and consolidated to form division bands.

Organization bands performed many non-musical duties as infantry units. Most bands guarded post perimeters and supply trains. They were able to function as musical units when required, as long as they remained organically intact and held occasional rehearsals. Many times, however, commanders would use their bandsmen as litter bearers or replacements in the line. When it came time to use these bands as musical units, they were generally inoperative and required several months to reorganize and retrain.

Field commanders used organization bands primarily to entertain off-duty combat troops. Commanders made their bands more versatile and maneuverable by dividing their bands into several small ensembles (similar to today's Musical Performance Teams (MPTs)). This also allowed them to perform closer to the front. Some ensembles, such as those from the 101st Airborne Division Band, played as far forward as command posts.

The 28th Infantry Division Band distinguished itself during WWII. During the Battle of the Bulge, the divisional command post at Wiltz, Luxembourg, came under severe attack. Members of the 28th Infantry Division Band took up arms and fought as part of holding line around Wiltz to stop the German advance. The band put away their instruments, dug foxholes and picked up carbines. A clarinetist manned a bazooka and then drove a truck loaded with the band's music. The clarinetist was going to save the music, but 10 miles out of Bastogne the convoy was ambushed and all the music burned. Only 16 of the band's 60 men survived the fighting in the Ardennes.

The 28th Infantry Division Band was not the only band involved in the Battle of the Bulge. The 101st Airborne helped hold on to Bastogne preventing it from falling to the Germans. The 82nd Airborne Division Band was caught in the battle after being sent to the Ardennes for R&R. The 82nd front line was stretched thin. The 82nd Airborne Band joined the depleted front line to hold off the German spearhead. The band helped hold off two German Infantry Divisions and a Panzer Division.

Because the demand for music units exceeded the number of available bands and ensembles, many commanders organized Field Music Units. Most Field Music Units, composed of drums and bugles played by Soldiers, spent their mornings on military duties, and afternoons in rehearsals or drill. These units became so popular, they performed extensively until the end of the war.

The war in Europe was not limited to just organization bands. The U.S. Army Band embarked on a two-week wartime tour in 1943, which lasted two years. The band performed near Metz, France not far from combat, to lift morale during the Battle of the Bulge. The Army Band performed at countless Red Cross and USO dances and played concerts for civilians. Of all the premier bands in Washington DC, The U.S. Army Band is the only one to ever perform in a theater of foreign combat operations.

Women's Army Corps (WAC) Bands. On July 20, 1942, the first contingent of women was inducted into the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) at Fort Des Moines, Iowa. By early 1943, five bands, the 400th Army Band, 401st Army Band , 402d Army Band, 403d Army Band, and the 404th Army Band were composed entirely of women. WAAC bands were later redesignated and officially activated in the Women's Army Corps (WAC) on January 21, 1944.

United States Ground Forces Band. In 1944, the War Department directed that a band be formed entirely of qualified musicians who had combat service overseas. Commanded by Chief Warrant Officer Chester Whiting, the new band was named the First Combat Infantry Band with a mission to entertain at War Bond Drives around the country. When it was no longer possible to maintain a band comprised exclusively of musicians with combat service, plans were made to reorganize and rename the band.

General Jacob L. Devers, Commander of the U.S. Army Ground Forces, issued the following order to Whiting: "I want you to organize a band that will carry into the grassroots of our country, the story of our magnificent Army, its glorious traditions and achievements, and of the great symbol of American manhood - the Ground Soldier." On March 21, 1946 the United States Ground Forces Band was activated.

During World War II, supervision of Army bands was divided between the Chief of Special Services and The Adjutant General. No central agency had full responsibility for the technical staff supervision of all Army bands and all Army bandsmen.

The Korean War. While the Army’s School of Music on Governor’s Island proved a successful partnership with the Institute of Musical Art in New York City, it was reorganized and moved to the War College in Washington D.C. in 1921, and ultimately closed in 1928 due to budget restrictions. Army bandsmen had no school from 1928 to 1941, but a School of Music was reopened in 1941 for a few years to train bandmasters under the shadow of a looming World War and trained more band officers than needed before being shuttered in 1944. Furthermore, the North Korean invasion of South Korea in 1950 delayed the implementation of a new band training program. The Department of the Army abruptly shifted its priorities to training and equipping men for action in Korea.

As in World War II, bands accompanied combat units into action. However, due to the constant infiltration, sabotage, and behind-the-line attacks by Communist troops, bandsmen were forced to participate in combat. Bands traveled many miles to perform several concerts a day for units close to the front line. One report read, "The closer we play to the front line, and recently we have been within a half-mile of it, the more enthusiastic has been the response to our music." As a result, bands rehearsed little, and performance quality declined.

Bands did distinguish themselves in the Korean conflict. Of ten Army bands serving in Korea, one received the Distinguished Unit Citation, six received Meritorious Unit Commendations, and six received Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citations.

In April 1950, The United States Army Ground Forces Band was renamed the United States Army Field Band.

In 1951, the Department of the Army established a 20-week basic bandsman course at the United States Navy School of Music, and an 8-week basic course at band training units located at Fort Ord, Fort Knox, Fort Jackson, Fort Leonard Wood, and Fort Dix. These 8-week courses were later increased to 16 weeks.

Post Korean War and the Armed Forces School of Music at Little Creek, Norfolk, Virginia. In February 1960, the 3d United States Infantry (The Old Guard) Fife and Drum Corps was formed as part of the Old Guard to support the musical requirements of the 3d U.S. Infantry, ceremonies conducted by the Military District of Washington, and Ceremonies of State. The Corps would primarily reflect the music of colonial America, making it unique from other Army bands. The instruments utilized by the Corps were the fife, bugle, and colonial drum which was kept tight by a rope tension system.

The drum major of the Corps carries an espontoon instead of the standard mace. He is the only soldier in the United States Army authorized to salute with his left hand.

On April 13, 1961, the Secretary of the Navy announced plans for the U.S. Navy School of Music to be relocated to the Naval Amphibious Base at Little Creek, Norfolk, Virginia. On August 12, 1964, the doors to the Navy School of Music in Washington, D.C. were secured. The USS Cado Parish and the USS Monmouth County proceeded to the U.S. Naval Amphibious Base loaded with musical instruments and Army and Navy personnel. Each ship had a band aboard to play honors as it passed George Washington's tomb in Mt. Vernon, Virginia. This was the first time an Army band performed honors on a Navy ship for our first president, George Washington. The ships landed at the Naval Amphibious Base on the morning of August 13, 1964. By joint service agreement, the facility was renamed the "School of Music" concurrent with the move. One of the highlights of the move of the School of Music was the dedication ceremony concert. Arthur Fiedler, conductor of the Boston Pops, guest conducted the School of Music Concert Band.

With the establishment of Enlisted Bandleader (E8) positions, a training program directed toward qualifying enlisted members for positions was programmed and implemented. This course became a prerequisite for the Warrant Officer Bandmaster Course of Instruction.

The Vietnam War. As the U.S. presence in Vietnam increased, bands once again prepared for combat. By 1969, eight bands were stationed in Vietnam. Seven of those bands belonged to divisions. They were assigned to the 1st, 4th, 9th, 23d (Americal), 25th, 101st, and 1st Cav Divisions. One Army band, the 266th, was assigned to the Army headquarters in Saigon. The RVN Armed Force Band Headquarters and Band School at Thu Duc Market Place oversaw the band program in Vietnam including administration, budget, training, and supply.

Bands in Vietnam, like those in Korea, often performed in combat areas. They flew into combat areas with instruments and weapons, prepared to play pop concerts or military ceremonies and to fight when needed.

In Vietnam, bandsmen built bunkers and served as guards for both inside and outside defensive perimeters, as well as being a vital part of pacification operations. While another unit screened people in a village for Viet Cong soldiers, bands presented concerts and a variety of entertainment to keep the noncombatant populace away from the screening unit. The people enjoyed the concerts, and the screening was completed without disturbance. Bands gave powerful psychological support to the troops in conflicts. The appearance of rock and jazz groups in remote areas assured combat soldiers they had not been forgotten.

One notable example of the use of bands in Vietnam was the "Thunder Road" incident, which received national publicity. Major General John Hay, Commanding General of the First Infantry Division, ordered his band to march down "Thunder Road" for a distance of one mile while playing the march "Colonel Bogey." This road was critical to the division, but was under the control of a North Vietnamese Army regiment located less than a mile away. The enemy, confused by the action, withdrew from the area. The band fulfilled a remarkable combat mission without firing a shot.

Bands were also used during the 1968 inner-city riots in the United States. National Guard Bands performed in the inner cities to calm the populace, and the 82nd Airborne Band assisted in controlling civil disturbances around Washington, D.C.

Army Bands in the 1980s. The 33d Army Band became the third separate band with a strength adjustment to 64 bandsmen and one commissioned officer bandmaster. The 33d Army Band is located at USAREUR headquarters and is commonly referred to as the USAREUR Band.

In November 1981, the Army published TRADOC Pamphlet 525-13, U.S. Army Operational Concepts Use of Army Bands in Combat Areas. TRADOC Pam 525-13 identifies the musical support provided before, during, and after combat. This publication also identified a secondary mission for Army bands. Bands assume the secondary mission when combat reaches an intensity that makes the primary music mission impractical. The secondary mission includes four areas.

(1) Command post security.

(2) Perimeter defense.

(3) Traffic control.

(4) Prisoner of war security.

On June 28, 1984, the Army established the Office of Chief, Army Bands at Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana. This office became the proponent for all matters pertaining to the Army Bands Program. With the establishment of this office, Army bands fall under the control of the Soldier Support Center.

In 1983, the School of Music ended its long relationship with the Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) as a separate service school and was integrated into the Soldier Support Center. All advanced courses underwent major revisions and aligned with the Noncommissioned Officer Education System (NCOES). NCOs were now able to obtain credit on their official military records for classes taken, something that was unavailable under the old system.

All bands were authorized as separate companies on 1 October 1985. Actions were started to withdraw all division bands from the AG Company of the division and reorganize them as separate companies. Separate and division bands were authorized 40 MOS bandsmen and 1 warrant officer.

In August 1986, Army bands were categorized into three different types: special bands, MACOM bands, and division/separate bands. The following bands were designated as special bands.

(1) The United States Army Band, Fort Myer, Virginia.

(2) United States Army Field Band, Fort Meade, Maryland.

(3) United States Military Academy Band, West Point, New York.

The following bands were designated as MACOM bands.

(1) The 50th Army Band (United States Continental Army Band), Fort

Monroe, Virginia.

(2) The 33rd Army Band, Heidelberg, Germany (USAREUR).

(3) The 214th Army Band (FORSCOM), Fort McPherson, Georgia.

Desert Shield / Desert Storm. The invasion of Iraq into Kuwait in 1990 brought the U.S. into conflict again. Bands once again distinguished themselves.

Eight bands saw duty in the Gulf War. They were the 1st Armored Division Band, 1st Cavalry Division Band, 1st Infantry Division Band, 3rd Armored Division Band, 24th Infantry Division Band, 82nd Airborne Division Band, 84th Army Band, and 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault).

In addition, two Army National Guard Bands, the 129th Army Band, and the 151st Army Band were activated to support Fort Campbell while the 101st Airborne Division Band was stationed in the Gulf. The two National Guard bands provided musical support to the families during the war. They also performed for troops returning from Desert Storm.

Bands' duties were varied. The 24th ID Band provided little musical support. The 3d Armored Division Band provided music up to and including the start of the war. The 3AD Band performed on the enemy side of a berm while the Division advanced into Iraqi territory. Many bandsmen spent countless hours guarding defensive perimeters.

Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) / Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF). The Army downsized considerably in the 1990s after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). In what appeared to be a more peaceful world, the need for a large standing Army appeared to dissipate and the Clinton administration abruptly shrank the Army and shuttered numerous installations and bands.

The Army’s shift to Brigade Combat Teams (BCTs) in the late 90s and early 2000s under “Force XXI” and “Transformation” brought about a radical modernization effort in Army Bands known as Future Army Bands (FAB) XXI. In an effort to stay relevant in the face of a changing Army, FAB XXI modeled the organization, home-station use, and deployability of Army Bands after the BCT concept within divisions and doctrinally removed the “secondary mission” of TOC Security espoused under the previous two conflicts. FAB XXI effectively allowed Army Bands to deploy in smaller components, focused on performing music while down range, while simultaneously supporting their home stations with other Music Performance Teams (MPTs).

The nearly twenty years of persistent conflict that constituted the War on Terror, especially Operations Iraqi Freedom, Enduring Freedom, and New Dawn, brought Army Bands into a new era of conflict participation. Every division band, numerous National Guard and U.S. Army Reserve bands, and even The U.S. Army Band “Pershing’s Own” deployed under the auspices of the War on Terror.

In those intervening years of conflict, as the Army’s counterinsurgency efforts required more special and unconventional forces, Army Bands proved to be a good bill-payer for those increases without busting the Army end-strength the U.S. Congress mandates. As such, numerous U.S. Army Reserve Bands and Active-Duty bands have been consolidated or inactivated since 2009, to include the 2nd Infantry Division Band, the 50th Army Band (The U.S. Continental Army Band) at Fort Monroe, the 62nd (M.I. Corps) Army Band, the 85th USAR Band, the 98th Army Band at Fort Novosel (formerly Fort Rucker), the 113th Army Band at Fort Knox, The 214th (FORSCOM) Band at Fort McPherson, the 392nd Army Band at Fort Lee, the Signal Corps Band at Fort Eisenhower (formerly Fort Gordon), and the Amy Material Command Band in Huntsville, AL. Additional cuts have been announced for the 11th Airborne Division Band in Alaska, the 77th Army Band at Fort Sill, the 399th Army Band at Fort Leonard Wood, MO, the U.S. Army Japan Band, and the TRADOC Band at Joint Base Langley-Eustis, VA.