By COL (Ret) Gary L. Gresh

Russia’s incursion into Ukraine in February 2022 reminded me recently of just how much history tends to repeat itself in world affairs. When I was just a newly minted Colonel fresh from the War College, I was assigned to Fort Bragg as the incoming 18th Airborne Corps Adjutant General, and then later assigned as the first Commander of the 18th Personnel Group, a new Brigade-like structure being fielded in 1990.

Never in a million years would I have thought I would actually soon be headed into a war zone. Fate has a way of throwing you a curve ball when you least expect it and perhaps when you are the least able to react and adapt quickly enough. That’s precisely what happened to me in August 1990, 32 years ago, on the eve of Operation Desert Shield, as I unpacked moving boxes in my newly assigned quarters on Fort Bragg, NC.

On the surface, Vladimir Putin’s “Special Military Operation” against Ukraine in February 2022, resembles Saddam Hussain’s incursion into Kuwait in 1990. But the strategic differences are immense. Kuwait is a tiny country with virtually no ability to defend itself against a well-armed enemy. At the same time, Ukraine is larger than Texas, with a modern but very young Army and Air Force.

Inserting America or NATO into Russia's Ukraine incursion would have been much more complicated than it was in Kuwait in 1990. For one thing, Russia is a nuclear-armed power, while Iraq was not. Secondly, inserting ourselves into Ukraine AFTER Russia had invaded the country might have invited a nuclear confrontation with Russia, something no power wanted to risk.

In the future, if the US wants to protect an ally through strategic power involving a nuclear-armed country, it would probably have to “beat the enemy to the punch,” so to speak, by inserting a “Training Team” into the targeted country BEFORE a possible enemy invasion. This would leave the enemy with a nuclear confrontation dilemma. This trip-wire defense was highly successful in Europe after WWII and Korea for over 40 years.

But you can be assured, no matter how this current world crisis may be resolved, YOU, the AG Soldier, must be prepared to pack your rucksack, kiss your loved ones goodbye, and board an aircraft en route to “God only knows where” to help a struggling democracy fight against totalitarianism.

Little did I know that day in August 1990, while continuing to unpack boxes, I would receive a telephone call from the Corps Operations Center asking me to report to the Headquarters immediately to meet with the Corps leadership team. I would not return to my Fort Bragg quarters until May of the following year, as we were quarantined, briefed, and began immediate preparation for deployment to Saudi Arabia to begin Operation Desert Shield, and subsequently, Operation Desert Storm in January 1991.

Iraq had invaded Kuwait, and the President designated the 18th Airborne Corps to go into Kuwait and force the Iraqi Army to go back home.

Fate had struck me again (my first deployment was in Vietnam), and this time I felt particularly unprepared. I had not even been to my office; I knew only a few of the assigned Officers and NCOs of the Corps AG Office, and I was utterly unprepared for the firestorm of activity with which I was about to embark. I was immediately plunged into the most stressful and action-packed preparation I had ever witnessed. I felt like a cork floating on a fast-running river, which I had absolutely no control over, and I knew nothing of where the river was taking me.

I had arrived at Fort Bragg ready to transition the Corps AG Office into the 18th Personnel Group, for which I had been selected as the first Group Commander. The Group was to stand up sometime between October 1990 and January 1991.

I next remember sitting in a 747 jet headed for Saudi Arabia with the advanced party of the Corps, a group of superb Officers and NCOs who would together begin the next 6 months of round-the-clock preparation to plan, receive, and set up a deployed Airborne Corps on the sands of Saudi Arabia, an absolute Human Resources nightmare of planning, coordination, and execution.

Since 1776, the American Army has run on paperwork – “forms” starting with the unit morning report of who was present, who was sick, and where all subordinate units were stationed. Nothing really changed in the Army from 1776 to 1980 regarding paperwork! We still shuffled paper to accomplish almost everything. When the 18th Corps deployed in August 1991, we had NO INTERNET, NO LAPTOP COMPUTERS, NO iPHONES, NO WI-FI, NO FACEBOOK, NO TWITTER, and perhaps the biggest of all, NO EMAIL! We did have a TV link with CNN on if we were lucky to get a connection.

The Army personnel community had been planning automation for almost twenty years, but everything was bulky and cumbersome and had to be connected by phone lines. The TACCS Box, the Army’s basic automation device, was the size of two foot lockers and required two Soldiers to load and unload it from any vehicle.

When we began leaving Fort Bragg on 10 August 1991, we were unplugged entirely from “the official Army personnel system” and SIDPERS. We only had the Fort Bragg database we had taken with us into Saudi Arabia. We had about a dozen TACCS computers with punch card input devices, each supporting about 500 troops, and absolutely no electronic connection with the Department of the Army except over long-distance phone lines. I was convinced that I was about to become the first-ever appointed 18th Personnel Group Commander to be relieved when Icould not tell the Corps Commander how many troops we had in country on any given day, let alone run casualty data or inbound replacements!

Lest I forget, it was not only those of us at Fort Bragg who were putting in 24-hour days, as all HR professionals in the Army were working overtime to help the effort. The Army DCSPER mobilized every personnel asset he could to help support the effort. Korea, Europe, the Reserve components, and the AG School Commandant ramped up to support the effort with deployed units, deployed individual fillers and replacements. The DCSPER himself, LTG Frederick E. Vollrath, called me several times by telephone to ask what I needed and how they could support our efforts. He was extremely concerned, as was I, about the enormity and impact of the forthcoming operation. However, it was a positive model of cooperation among personnel support agencies.

Pulling from the basics of Personnel Doctrine, we knew we had four core competencies and seven functions we had to be prepared to accomplish while protecting, sustaining, and caring for the Soldiers assigned to us to execute the theater personnel mission. I soon learned that giving only mission-style orders and allowing individual ingenuity and innovation to run wild among the company-grade officers and NCOs was the only way to succeed in this environment. You just had to trust your subordinates until or unless they proved unworthy.

Our NCOs were phenomenal! That’s where the US Army has a massive advantage over the Russian Army, still trying to conquer Ukraine. The Russian Army has no middle leadership like our NCOs.

I will now concentrate on the four most demanding tasks we had to overcome while trying to support a deployed and growing Corps: Organization, Automation, Mail, and Logistics. You must be prepared to change on the fly, innovate, and allow junior officers and NCOs to do their jobs.

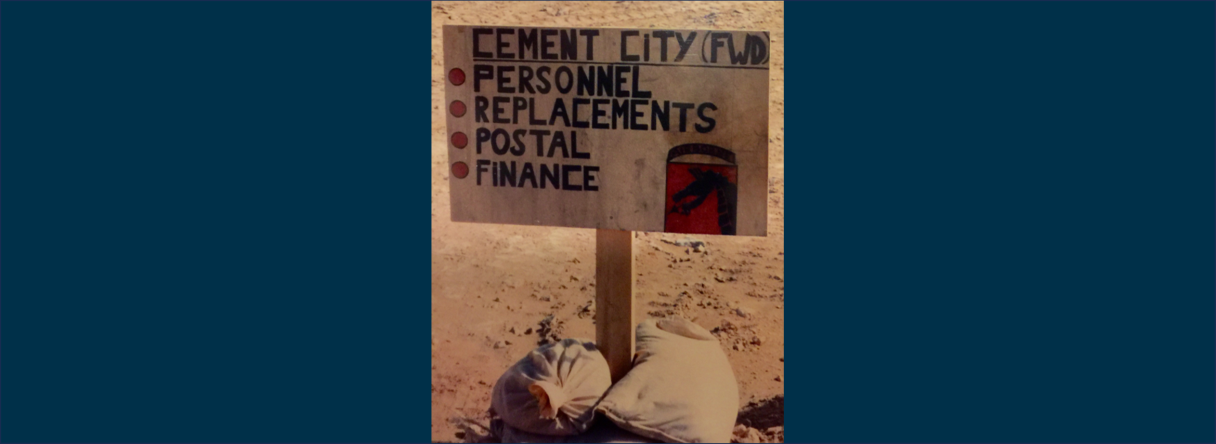

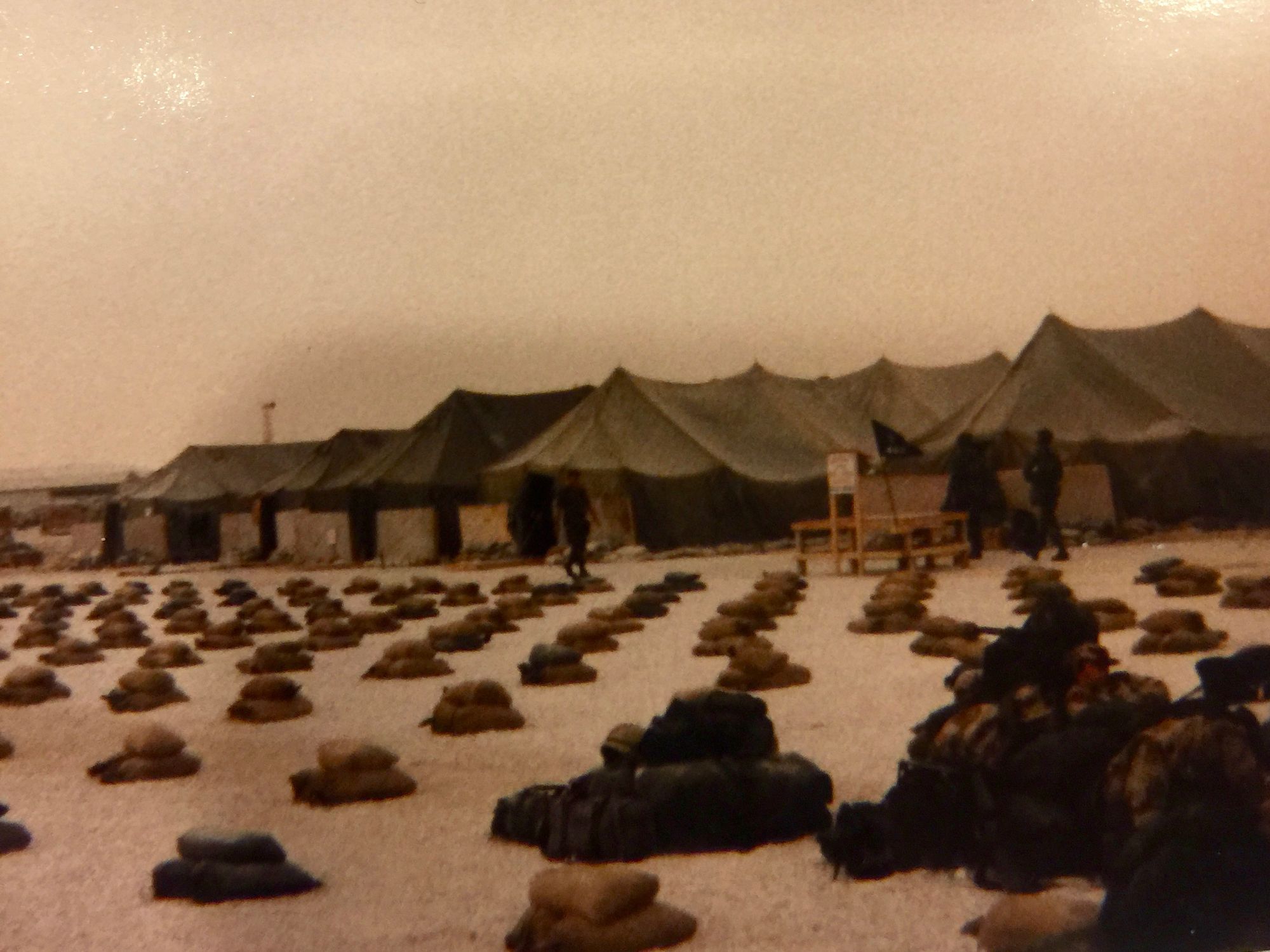

ORGANIZATION: We had none. We deployed as an AG section only to find all of our personnel assets were spread across the Corps Support Command with little in the way of vehicles and life support to stand on their own as we transitioned to a Personnel Group Structure. Innovative Company Grade Officers, NCOs, and Professional Civilians came together to advise, plan and support the construction of a Group structure while deployed in a combat zone within Saudi Arabia. The Army DCSPER and MILPERCEN provided individual fillers as needed to flush out a Group Staff, and the P&A Battalion Commanders and their staffs came together to form an effective Group structure. The Corps Commander decided to form the Group early and to detach all units from the COSCOM so that the COSCOM could focus on its colossal mission of bringing ammunition and supplies into the Corps. This left the Personnel Group on its own to form, set up operations, and support itself as it almost doubled in size weekly. The Officers and NCOs took on this challenge with absolute resolve and “Got-it-Done!”

AUTOMATION: We had some. We had 12 TACCS Boxes loaded with the basics of the Corps Headquarters. But we needed a much bigger database, which we did not have, nor did we have the capability to store such a vast database. Once again, the American Army NCO stood up to the challenge. The head of my SIDPERS section politely asked me to go get some coffee while they pondered the situation and came up with a proposal to solve the problem. Their solution was absolutely brilliant. They coined the phrase “Five Digit Midget” or "FDM." The “FDM” changed the coding in the TACCS box to hold only five pieces of critical information on each soldier in the Corps: Name, Rank, SSN, MOS, and Unit of Assignment.

These essential elements were needed to report strength accounting, location, casualty, and units. It allowed the SIDPERS section to dump thousands of pieces of information currently stored in the TACCS boxes, thus allowing much more room in the database. By linking the TACCS boxes together in tandem, much like a string of Christmas tree lights, our team could use these same TACCS boxes to upload an entire Corps database. This required placing HR Soldiers at every incoming air and sea terminal to collect the five pieces of information from manifests as units landed. We also deployed LNO teams to each hospital and aid station to collect casualty data. All of this was made possible by the DCSPER and MILPERCEN, who sent us NCO fillers from Korea.

Meanwhile, largely unknown to us, the DCSPER was pulling out all the stops to buy and deploy to theater recently produced laptop commuters by Dell as quickly as possible to give us a database capability. These laptops would eventually arrive in our area from December 1990 to January 1991. In the meantime, the brilliant database built by the 18th Personnel Group and 18th P&A Battalion NCOs stood the test of time.

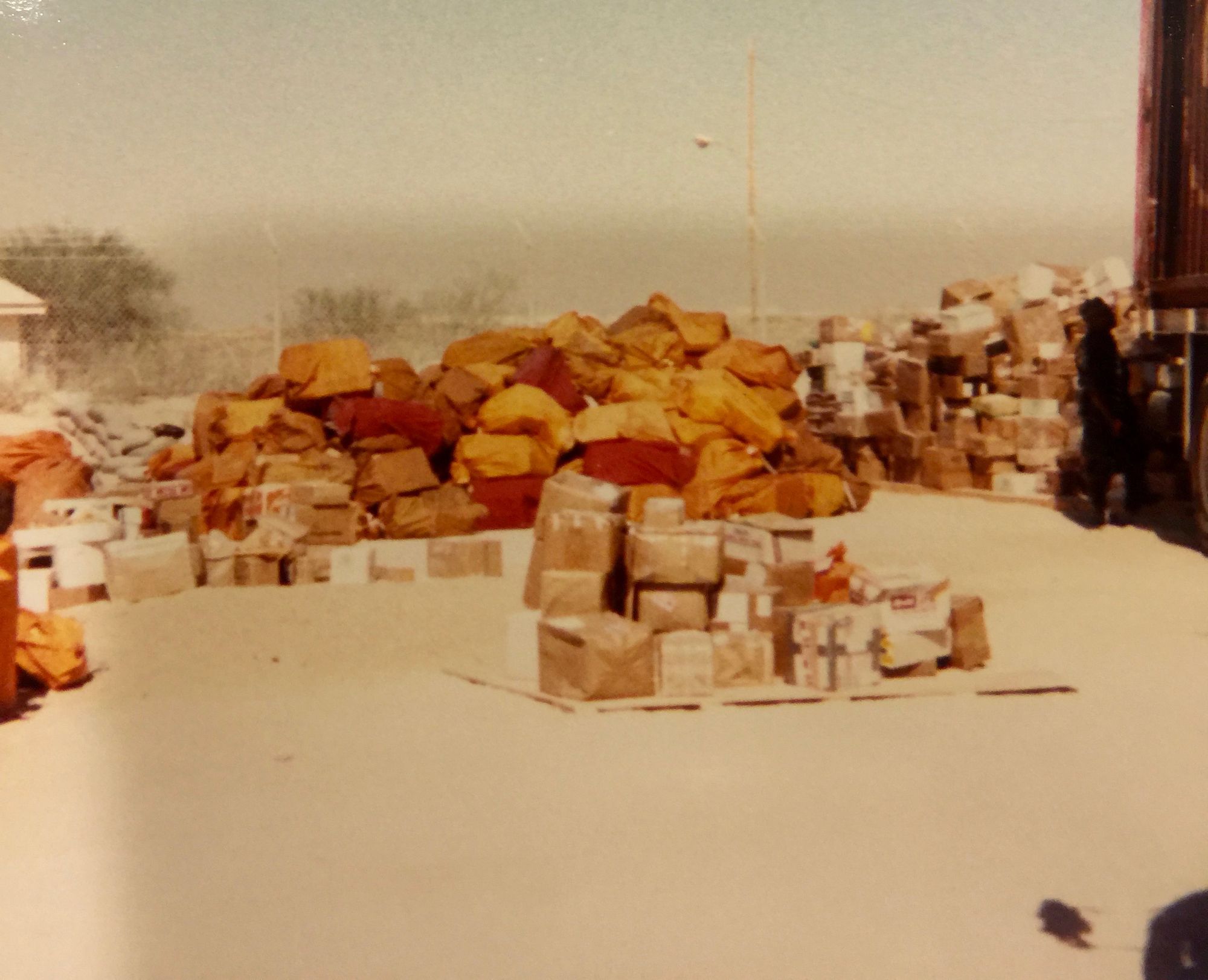

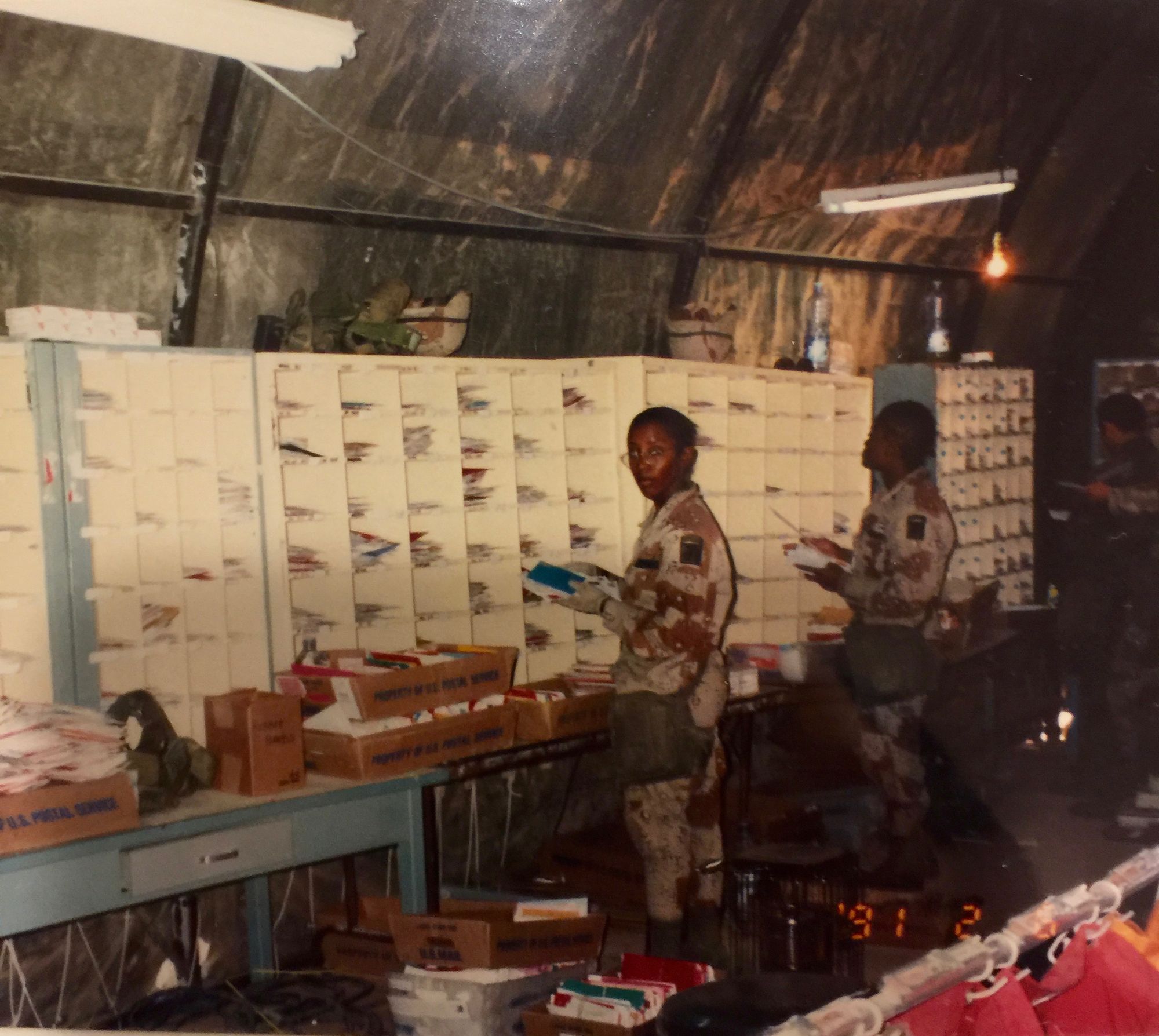

MAIL: Yes, we had Mail. Perhaps our biggest challenge was the US Mail system! Even in 1991, Army Soldiers still penned handwritten letters and dropped them into the US Mail to loved ones back in the states. There was NO EMAIL, NO TEXT MESSAGES, NO FACEBOOK, NO TWITTER, and lastly, there were only a few phones to call home. Perhaps even worse, stamps in 1991 were of the LICK-EM and STICK-EM type, quickly becoming a mass of glued paper in Soldiers' sweaty pockets in Saudi Arabia. The DCSPER helped us by getting Congress to pass free mail. Today, you will still have handwritten mail and packages, but I recommend you prepare for what you must do when the WI-FI fails, and EMAIL does not work, because it will happen in wartime. Fate, to be sure, has a plan! It's worth noting that postal personnel and unit assets alone would account for almost 35% of the Group by the time the deployment ended. The 18th Personnel Group quickly became the largest deployed Personnel Brigade in history since WWII.

REPLACEMENTS: The 18th Personnel Group became the largest unit in the Corps rear when over 1,700 personnel replacements began arriving through our Replacement Detachments. We fed, housed, and supplied newly arriving troops. The Reserve component quickly became the Corps's savior, sending Postal Companies, fillers, Mess Teams, US Postal employees, and mail sorting equipment to the Group.

Then fate struck again. A wonderful columnist named Ann Landers decided to print a series of articles in every newspaper in the country telling Americans that Soldiers, particularly women Soldiers, needed personal sanitary toiletries and to send them addressed to ANY SOLDIER, 18th Personnel Group, Saudi Arabia! Tractor-trailers began delivering tons of boxes to the theater to be distributed to Soldiers, requiring forklifts and huge storage areas to place and sort the shipments. Thank God it does not rain often in Saudi Arabia, as all of these packages had to sit out in the weather until distributed.

LOGISTICS: The Group had little in the way of logistics personnel, vehicles, tentage, mess facilities, or even office basics such as tables and chairs. Thankfully, the DCSPER, in conjunction with the DCSLOG and Fort Lee, started funneling supplies and logistics to the 18th Personnel Group as quickly as possible. However, this required officers to construct handwritten property books and ways of tracking supplies and equipment. This challenge was with us every day until the end of the deployment and even had us setting up Arms Rooms and secure storage facilities for weapons that were funneled back to the 18th P&A Battalion Replacement Detachment from hospitals and aid stations that could not hold them while on the move. Remarkably, only two survey reports were needed at the end of the operation to account for the few lost items during the deployment.

Desert Shield and Desert Storm was the first ever overseas deployment of an entire Army Corps in less than six months, with many units taking their own equipment and many deploying without TOE equipment, requiring Reserve Component Depot support from across the USA. Every day felt like you were inside a blender being spun in 100 different directions at once. But incredibly, the Officers, NCOs, and Soldiers of America made it all happen. It was an honor to serve with every one of them. It’s amazing what you can accomplish when you unleash the potential and ingenuity of the American Soldier.

About the author - COL (Ret) Gary L. Gresh (Greshg@bellsouth.net), Author, Amazon Books Publishing. COL (Ret) Gresh is an AG Corps Hall of Fame inductee, Class of 2011, and a Distinguished Member of the Corps. COL (Ret) Gresh served in many AG, Special Forces, Ranger, and Airborne Units. He commanded at every level, from a Platoon Leader in Vietnam in the 101st Airborne Division to the Commander of the 18th Personnel Group out of Fort Bragg, NC, during Operation Desert Shield / Desert Storm. During his 30 years of service, he earned over 24 awards and decorations in the Army, including the Distinguished Flying Cross, Two Bronze Stars, and the Legion of Merit. The Secretary of the Army awarded COL (Ret) Gresh the U.S. Army Distinguished Service Medal upon his retirement as the 20th Commandant of the Adjutant General School and the 7th Chief of the AG Corps.